In 2020, LEEP set out to eliminate the market availability of lead paint in Malawi. We found evidence of high levels of lead in market-available paint and presented the results to the Malawi Bureau of Standards, who then committed to enforcing lead paint regulation. LEEP is now supporting the Bureau’s enforcement efforts and helping manufacturers switch to lead-free paint.

But by how much, and how cost-effectively, will this program advance LEEP’s mission to end childhood lead poisoning? Using data and a number of assumptions, we conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) to try to answer this question.

This is a tricky task; quantifying impacts always presents challenges. Here it requires predicting the future that our efforts bring about in Malawi, as well as comparing that future to what’s known as the “counterfactual” – the alternative future of what would have happened, had LEEP not intervened.

Nevertheless, we believe a preliminary CEA could be valuable in two ways. First, at LEEP, we aim to improve people’s lives as much as we can. CEAs serve as one tool to guide our decision-making, such as in determining where LEEP might have the biggest impact. Second, LEEP is powered by grant and donor money. A CEA is one way to hold us to account and show that we are spending our funding effectively.

This post is an introduction to our model for evaluating the cost-effectiveness of LEEP’s Malawi program. Here we describe the model’s overall structure but do not go through all of our parameters and assumptions. For more details see the model itself and the accompanying documentation.

$14 per year of healthy life or equivalent

215,000 fewer children exposed to lead

$180 million saved in lost earnings

by 2041, projected

How do we define cost and effectiveness?

To model cost-effectiveness, we have to decide what counts as a “cost” (the resources used by or because of LEEP) and what LEEP intends to be “effective” at (the benefits brought about by LEEP). We define costs as the monetary costs incurred by LEEP and by the Malawi government. Our estimate is that LEEP will spend $80,000 annually for the first five years on its Malawi program, while – if LEEP succeeds in its aim – the Malawi government will spend $75,000 annually for the first eight years to implement regulation.

In a way that facilitates comparisons with other global health interventions, we define LEEP’s effectiveness as the negative outcomes averted by its work. Lead negatively affects children’s wellbeing in two main ways: first in harming their physical health, leading to premature death or physical disability, and second in permanently impairing their cognitive abilities, leading to lower productivity and hence lower earnings throughout their lives.

The first effect is quantified by the World Health Organization using disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Each unit (one DALY) represents the loss of a full year’s health. The second effect is measured by the loss of income, which we rely on value judgments to convert to units equivalent to DALYs (DALY-equivalents). In particular, we follow GiveWell and equate one DALY to 2.8 years of income. We therefore use the total number of DALY-equivalents averted to quantify our effectiveness.

What does it mean to avert DALY-equivalents?

We anticipate that our program will significantly reduce the number of houses painted with leaded paint, which will in turn reduce the number of children in Malawi exposed to lead per year. Ultimately, this lowers the total number of DALY-equivalents caused. But even in the counterfactual case, we would expect that, some number of years in the future, Malawi would have begun to regulate lead paint anyway and reap similar benefits.

LEEP’s effect is therefore not to generate lead paint regulation in Malawi when it otherwise never would have existed, but rather to expedite it by some number of years. With a fair amount of uncertainty (more on this later), we estimate this to be eight years. “Averting” DALY-equivalents means shrinking the number of DALY-equivalents that would have otherwise been caused.

How cost-effective is LEEP’s Malawi program?

To calculate the number of DALY-equivalents our program will avert, we refer to data and modeling from two research studies. The impact of lead poisoning on physical health is estimated in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, while the scale of its economic ramifications for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is assessed in a widely cited 2013 study. We then make an assumption about the proportion of lead exposure caused by paint rather than other sources (more on this later too).

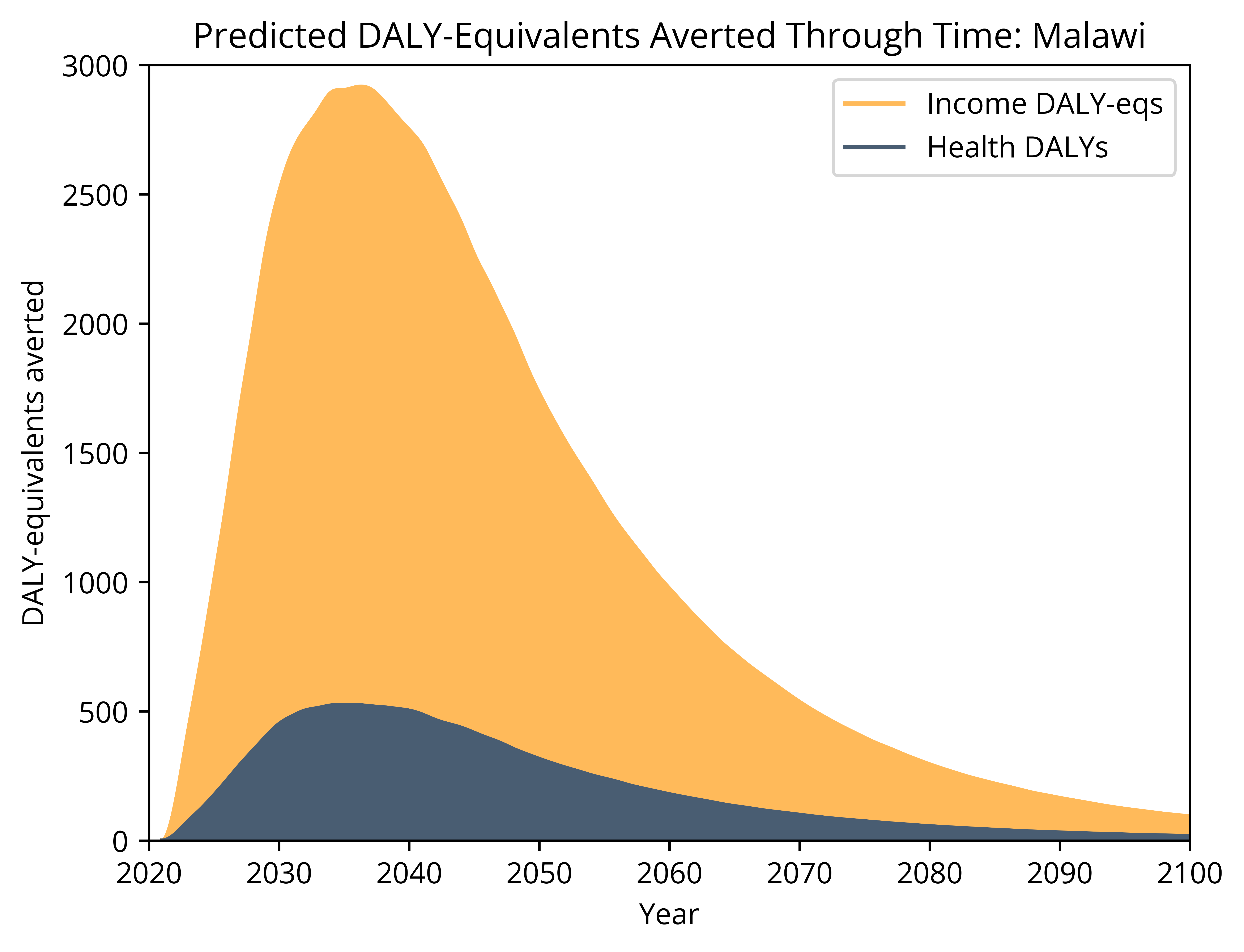

Our calculations show that, over the first 20 years, we can expect to avert ~43,000 DALY-equivalents in Malawi. Of these, improved health outcomes account for about 20% (~8,000 DALYs averted), while increased income accounts for the other 80% (~35,000 DALY-equivalents averted). It’s important to note that these figures are time-discounted, meaning we choose to value benefits slightly less going further into the future (again, more on this later).

We can also consider figures that may be easier to relate to. In terms of health, ~8,000 DALYs roughly represents lead poisoning being averted in ~215,000 fewer children in Malawi over the course of the next 20 years. And in terms of income, ~35,000 DALY-equivalents equates to ~$180 million saved in lost earnings throughout the lifetimes of children affected by the program.

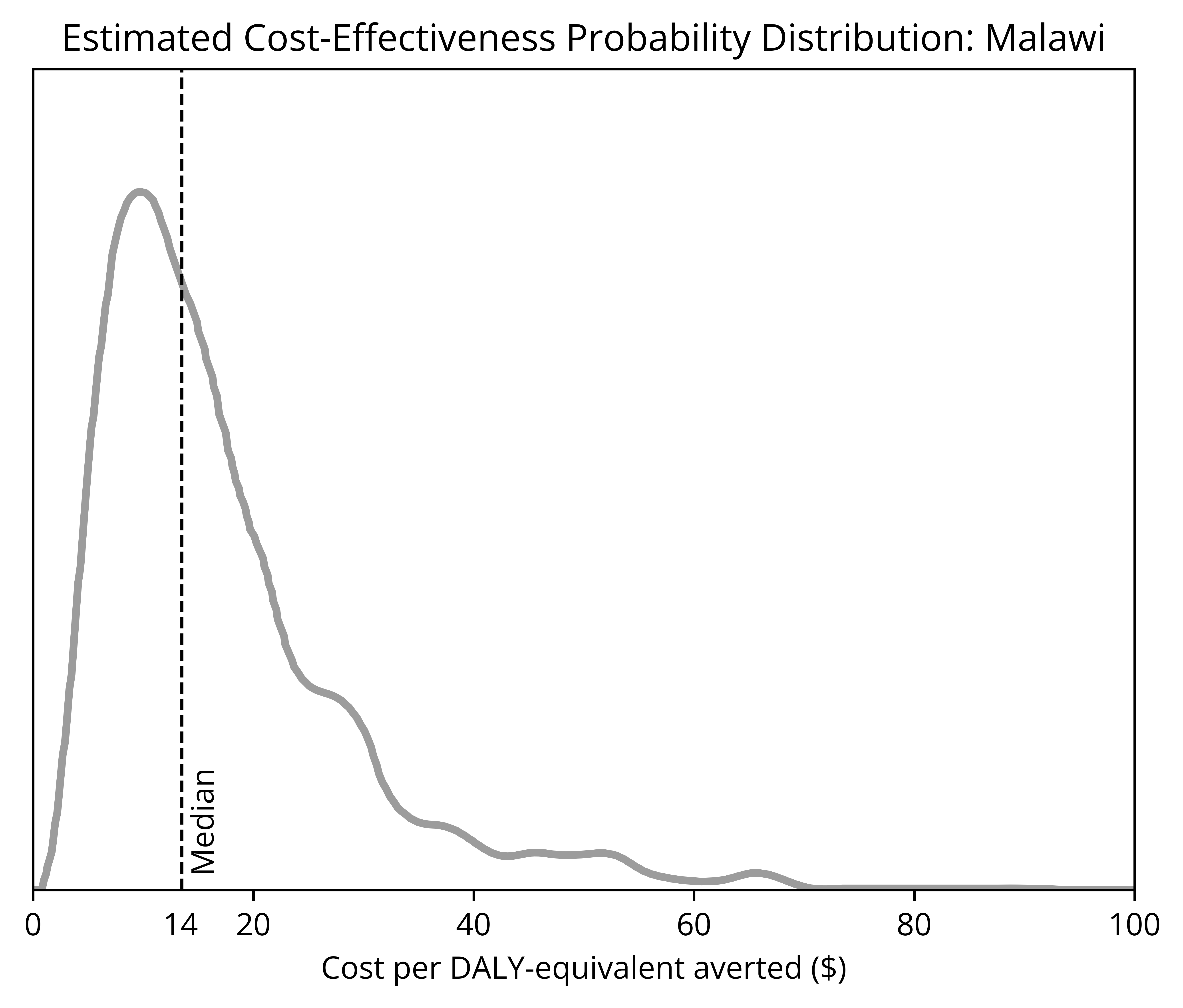

Over the same period, we estimate spending will amount to ~$590,000. (Similarly to benefits, these are discounted for factors like time.) Putting together estimates of costs and benefits and running thousands of so-called Monte Carlo simulations to account for uncertainty in the model, we find the median cost-effectiveness of LEEP’s Malawi program to be $14 per DALY-equivalent averted, a very promising result. In the graph below, we show the median result and uncertainty distribution, indicating the range of values of cost-effectiveness predicted by the model.

What do these preliminary results mean?

Approximately 20% of the total benefits are due to health improvements and 80% due to higher incomes, showing that the poverty-alleviation component of our work is significant. In the 2013 study on which we based our income-effect calculations, researchers calculated that LMICs lose approximately $1 trillion each year, or more than 1% of their total GDP, due to lead poisoning alone.

Also notable is how our CEA suggests LEEP’s effectiveness is distributed across time. Recall that averting DALY-equivalents means reducing them relative to the counterfactual scenario. In practice, this means that the LEEP’s effectiveness rises to a peak before tapering off as the effects of counterfactual actions start to kick in.

Lastly, we can consider a cost-effectiveness of $14 per DALY-equivalent in the broader context of programs within global health and development. Take, for example, GiveDirectly, one of GiveWell’s top-rated charities. Like LEEP, it raises the incomes of people in low-income countries, but does so by giving unconditional cash transfers. Applying a unit conversion to a CEA by GiveWell, we find that GiveDirectly has a cost-effectiveness of approximately $836 per DALY-equivalent averted. (It’s important to bear in mind that this comparison is not exactly like for like, since GiveDirectly’s program has been studied extensively and is operating at a much larger scale than LEEP’s.)

Where could our analysis go wrong?

Investigating the uncertainties in our model allows LEEP and other decision-makers to judge how much to trust the estimates of cost-effectiveness and to decide whether to seek more information to fill in present gaps in understanding. Here we briefly describe three important uncertainties. (Further analysis is provided in the model documentation.)

The model hinges on the proportion of lead exposure in Malawi that is caused by lead paint as opposed to other sources, which is highly uncertain. While research suggests that lead paint causes 70% of childhood lead exposure in the US, no such estimates exist for LMICs. For Malawi, we therefore use the conservative estimate of 20%. If the actual proportion in Malawi were only 5%, the median cost per DALY-equivalent averted would rise to $48.

We’re also not certain about the number of years by which LEEP will have brought regulation forward; we chose eight years because no one else – to our knowledge – was working on the problem in Malawi, and the Bureau of Standards indicated that action would not be taken without evidence that lead paint was a problem. Reducing the eight-year figure to, say, five years raises the median cost per DALY-equivalent averted to $18.

As with all cost-effectiveness analyses that model changes over time, the result depends on the time discount we choose. For future costs and benefits, we apply a 4% per year time discount, in line with GiveWell. Because some of the effects of preventing lead exposure – like raising incomes – will happen many years into the future, the time discount chosen can quite significantly change the results. For example, applying a 7.5% time discount would increase the median cost per DALY-equivalent to $34.

The uncertainties described above all concern the model as we’ve constructed it. If one were to estimate cost-effectiveness in a different way, such as by starting from an assumption of how many walls are painted with lead paint in Malawi (rather than the proportion of lead exposure caused by paint), the results would differ. In order to increase the confidence in our initial calculation, we’re eager to compare our results with those anyone else might produce.

Summary

Despite its preliminary nature, this CEA for LEEP’s Malawi intervention paints a highly promising picture, putting the cost per DALY-equivalent averted at $14. This figure compares favorably with those for other programs. But even given that, it’s easy to lose sight of what it really means: $14 is a tiny amount to pay for the equivalent of an extra year of life at full health. While we recognize our findings are tentative, this result heightens our motivation to continue our mission to end childhood lead poisoning in Malawi and beyond.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

James Hu

James studies Earth and Environmental Science at the University of Chicago. He has interned at LEEP since September 2021 and is interested in effective altruism, earth systems, and environmental health. He recently carried out a field-based research project on the sources of lead contamination in a Massachusetts salt marsh, with the Marine Biological Laboratory. He can be contacted via y.james.hu@outlook.com and linkedin.com/in/y-james-hu.