Introduction from LEEP’s Co-Executive Directors

2024 was an exciting year for LEEP, as well as the wider field of actors working on lead poisoning. We continued to scale our lead paint programs, supporting governments and industry to eliminate lead paint from markets across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. We were delighted to meet our overall 2024 goal to make a significant step to eliminate new lead paint across countries representing 45% of births in low- and middle-income countries.

To share a few notable highlights: on the government side, Nigeria implemented enforceable lead paint regulation in March 2024, following advocacy efforts by our partner SRADev Nigeria—a significant advancement, particularly on a global scale, given that Nigeria is the sixth most populous country in the world and Africa’s second largest paint market. On the industry side, a majority (by market share) of lead paint manufacturers are now taking active steps toward reformulation in 10 countries, spurred by our work. In other words, in these 10 countries, most of the lead paint market is on the path to becoming lead-free, which we estimate would avert lead poisoning in at least 700,000 children.

Our monitoring continues to demonstrate the impact of this work. In Malawi, since last year, three more manufacturers have switched to lead-free formulations, with the remainder of the market currently in transition. In another large program country with over 200 million residents, we’ve seen the market share of brands selling lead paint for home use decline substantially—from 87% in 2021 to 58% in 2024.

Juliette Finetti joined LEEP as Director of Research and Strategy and has been conducting a research review and building our strategy across sources of lead exposure. Looking to 2025 and beyond, we will continue to hone and scale our paint program while ramping up work on other sources of lead exposure, such as cosmetics and spices. Our vision is to develop effective interventions for these additional sources and scale them, applying the approach that has proven effective with paint.

It’s been gratifying to see and be a part of the increased attention on lead exposure in 2024. For example, we shared our approach and learnings with the Partnership for a Lead-Free Future (PLF), both during its development phase and at its launch on the sidelines of the 79th UN General Assembly.

The progress we’ve made would not have been possible without our team, partners, advisors, and donors. Thank you to everyone who has supported LEEP. We remain committed to our vision of a world where every child can reach their full potential, free from the effects of lead poisoning.

Lucia and Clare

Our work in 2024

Our goal is to reduce childhood lead poisoning as much as possible – i.e. to have a large-scale positive impact. In this section, we describe the progress we made in 2024 in our paint programs, and in other strategic projects, such as in exploration of non-paint sources of lead exposure and in local and global collaborations.

Paint programs

Initiated paint programs

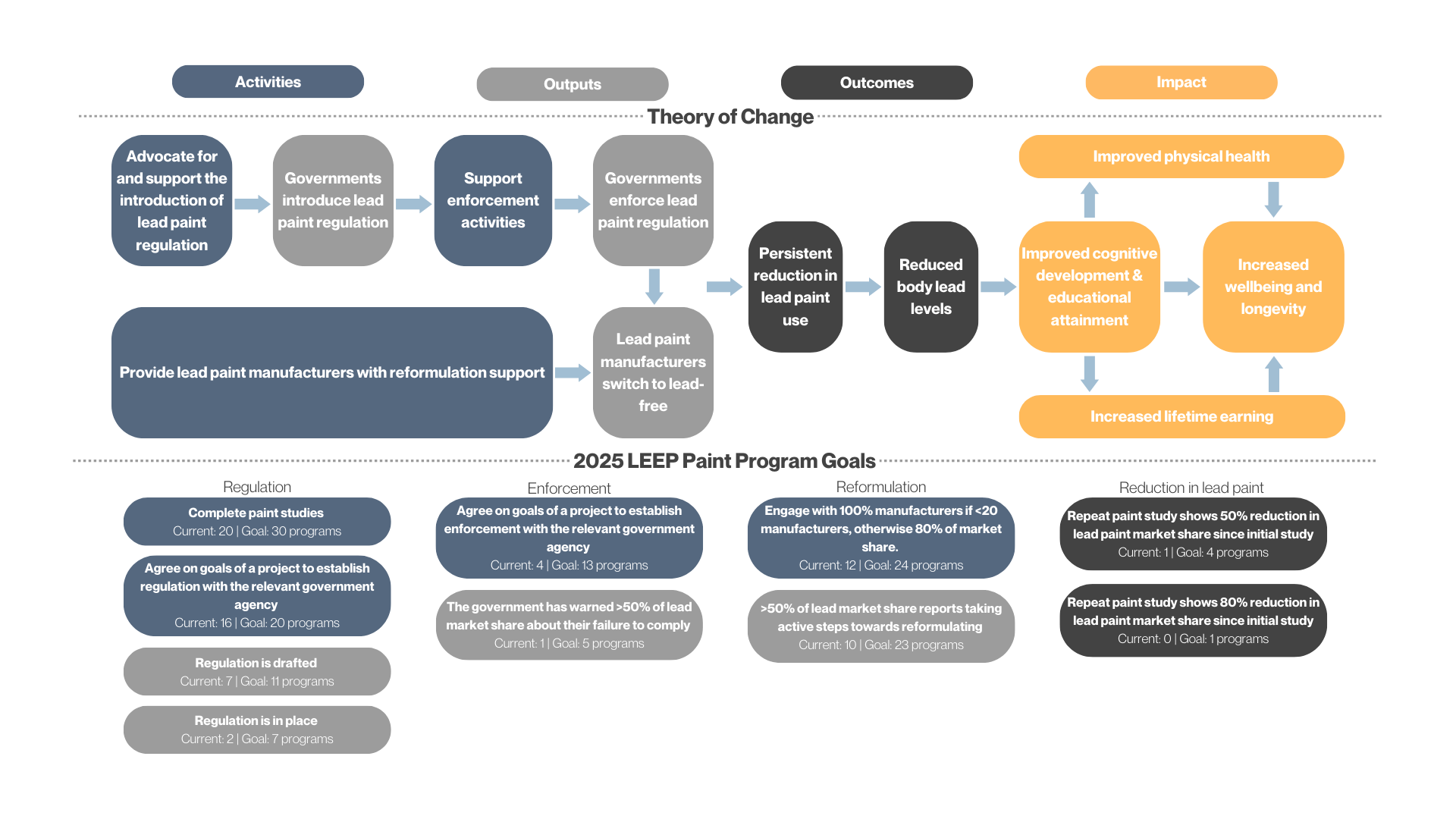

The theory of change shown below explains how our paint programs aim to reduce the use of lead paint, thereby reducing lead exposure, and improving children’s health, potential, and wellbeing.

As outlined last year, our goal is to have started paint programs in countries representing 75% of births in LMICs by the end of 2026. To achieve this, we planned to start new programs in approximately 10 new countries each year between 2024 and 2026. In 2024, we started 11 new programs in countries across Latin America, Africa, South Asia and South-East Asia, taking us to a total of 31. These countries represent approximately 59% of births.

Completed paint studies

Collecting data on the lead content of paint is a crucial element in our paint programs. The data motivates and informs the development and enforcement of regulation. Assisting with paint studies is frequently one of the top requests from our government partners, and the findings can directly support enforcement efforts. These studies also enable us to focus on countries with the highest levels of lead paint, prioritize manufacturers based on their impact and need for technical reformulation assistance, and assess progress toward eliminating lead paint from the market through follow-up analyses.

In 2024, we completed baseline paint studies in seven countries: Burkina Faso, Burundi, Kenya, Peru, India (Karnataka State), Rwanda, and one country that we are not yet able to share. Across the board, we have found that lead pigments are still commonly used in coloured, oil-based paints. Lead driers are also used in some cases. Several more studies are underway – in Egypt, Mexico, Türkiye, and Viet Nam.

Follow-up studies are also underway in three programs. In Malawi, following on from our results in 2023:

- Another manufacturer has switched to lead-free.

- Two other manufacturers have reformulated to new pigments, reducing their paint to almost lead-free – there are some final contamination issues that need to be resolved.

- The two remaining manufacturers have both placed bulk orders for lead-free pigments, and expect to have reformulated by mid-2025.

This suggests that Malawi’s paint market is very close to being completely lead-free. Our review of studies conducted by IPEN and LEEP finds that 70 out of 73 LMIC countries have lead paint for home use available on the market, which indicates what a remarkable achievement this would be for Malawi.

In another major program country with over 200 million residents, our re-testing shows the market share of brands selling lead paint for home use has declined from approximately 87% in 2021 to 58% in 2024. We are anticipating a further nine percentage point reduction in the near future as a large manufacturer has significantly reduced levels of lead in its paint and is working closely with LEEP to move to lead-free. Due to the size of this program country, this progress corresponds to lead exposure reduction in a very large number of children.

Supported governments in implementing lead paint regulations

We work closely with our government partners to offer technical and financial support for implementing lead paint regulations. In addition to paint studies, this includes funding meetings and workshops, sharing educational and technical resources, providing training, and building testing capacity.

In July 2023, LEEP was pleased to award a grant to Sustainable Research and Action for Environmental Development (SRADev Nigeria) to support lead paint elimination in Nigeria through government advocacy and industry engagement. We are delighted that, as a result of meetings and a workshop as part of this project, lead paint regulation was signed and gazetted in Nigeria, making it an enforceable law from March 2024. Nigeria is the sixth most populous country in the world, and the second largest paint market in Africa, so this represents a huge step forward in preventing lead paint exposure.

Liberia also passed lead paint regulation in January 2025, after finalising and validating their draft regulation at a series of workshops funded by LEEP in October and December 2024. Congratulations to the EPA and NPHIL for their work on this!

On the enforcement side, we signed agreements with the PSQCA in Pakistan and the Malawi Bureau of Standards to work together on lead paint conformity assessment. The agreements set ambitious targets for reducing lead levels in paint and aim to strengthen enforcement by offering LEEP-funded testing. We ran our first enforcement training in 2024 with the Malawi Bureau of Standards, partnering with Instiglio. This workshop trained factory inspectors to identify lead ingredients, emphasising sampling of brightly coloured paints. We also provided a tailored factory inspection checklist to improve their inspections. Since then, the Malawi Bureau of Standards has sent warning letters to non-compliant manufacturers, demonstrating their commitment to the issue.

Provided technical assistance to help paint manufacturers reformulate, and received reports of their switching to lead-free paint

Supporting paint manufacturers in transitioning to lead-free materials is a core prong of our program, particularly in areas with limited enforcement capacity: it works to ensure the market is moving towards lead-free, while also increasing industry backing of and compliance with regulations. Our assistance includes consultations with a paint technologist, identifying low-cost, locally available alternatives, providing free samples and testing, and offering guidance on using the lead-free pigments.

We’ve found that one of the most useful things we can offer is a viable list of alternative, lead-free pigments for manufacturers, which are locally supplied. In order to build up our list, we attended coatings shows in India, Pakistan, Mexico, UAE, China, and Türkiye this year, connecting with suppliers and distributors operating around the world. LEEP has engaged with 200+ manufacturers and distributors of pigments, conducted pigment testing on over 70 pigments, and can now connect lead paint manufacturers with over 10 different suppliers of lead-free pigments.

In 2024, we successfully engaged with the vast majority of lead paint manufacturers (by market share) in nine more programs (bringing this total to 12 programs, up from three). In addition, over 50% of the lead paint market share report taking active steps to reformulating (such as ordering replacement pigments) in five more programs (10, up from five).

Other strategic projects

Effectively executing our paint programs at scale currently represents the vast majority of our work, but there are several wider projects that work towards our ultimate goal of reducing lead poisoning. In particular, we are excited to grow our work on non-paint sources of exposure in 2025.

Research project to reduce barriers to lead in paint testing

We were awarded a grant from the Lead Exposure Action Fund for a joint project with academics at Stanford and Mercer Universities to validate readings from portable x-ray florescence devices against more sensitive instruments and, based on this, to develop a standard method of using XRFs for lead paint testing. The cost, need for trained personnel, and time-consuming process of current methods of lead-in-paint testing are all important barriers to regulatory authorities enforcing lead paint laws. The aim of this project is to reduce these barriers. We contributed to this paper, which demonstrates the viability of the method. Our project partners have been working with ASTM International, a standards organisation, to make this a recognised standard method.

Grants program

As part of International Lead Poisoning Prevention Week 2024, we ran a grants program. ILPPW is a global, participatory campaign that has been organised by the WHO since 2013. It provided an opportunity for LEEP to support locally driven projects to reduce lead poisoning. We offered funding for activities that we have found to be important along our theory of change, such as paint studies or government workshops to make progress on regulation. We received 87 applications and awarded eight grants, totalling $30,000, to NGOs or government agencies in Congo Republic, Ecuador, Honduras, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, The Gambia, Tunisia, and Zambia, for activities including: paint and spice studies, industry awareness raising activities, and government advocacy workshops. We will review the impact of this project in more detail, but it has already demonstrated a potential route to reaching an even wider scale.

Work on non-paint sources of exposure

In 2024, we aimed to spend roughly 5% of our resources on this area. In April 2024, we decided to work towards investing more on non-paint sources in future years, so we hired Juliette Finetti to be LEEP’s Director of Research and Strategy.

Our motivation has always been to maximize our impact. We’ve developed and scaled a successful program for lead paint—we want to know if we can apply the same rigorous, experimental approach to other sources. We believe we’re well positioned to do this, partly because governments often see paint as just the starting point and are eager to tackle lead exposure more broadly. In some cases, it’s also logistically simple to extend our work—for example, testing cosmetics alongside paint during studies. In 2024, we ran small-scale tests on spices and cosmetics as part of our paint programs. While we can’t share results yet, we’re excited about the potential to broaden our reach and find new solutions.

In order to identify the highest impact opportunities outside paint, we conducted a shallow review of all known sources of lead exposure and assessed their promise against a set of criteria: i) evidence that LMIC populations are exposed to lead via this source, ii) magnitude of the blood lead level impact of exposure, iii) scale of the issue, and iv) feasibility of addressing the issue. This required a rapid literature review of studies documenting the presence of lead in each source, its prevalence, and potential pathways through which exposure translates to lead in the blood. Based on this, we estimated their impact on blood lead levels using a combination of observational studies and existing estimation methods such as the biokinetic model used by the US Environmental Protection Agency. Finally, we searched for information on consumer behavior, characteristics of the industry, and market structure to assess the feasibility of LEEP making progress on the issue through a new program.

We shortlisted four sources of lead exposure–three of which are consumer products–that appear promising across all our criteria:

- Lead-adulterated spices have a strong enforcement track record, but further research is needed to determine the global scale of the issue beyond the known hot spots.

- Unregulated lead-acid battery recycling poses severe health risks, with extremely high blood lead levels observed near recycling sites. While the severity makes it a promising issue to work on, our uncertainty is on the potential scale of impact. Because cleanup requires significant resources and expertise, our influence in this industry would likely primarily come from strengthening standards for future sites— limiting our impact to populations living near future sites.

- Plastic dishware is widely used in Sub-Saharan Africa, and there is strong evidence that lead compounds are involved in its production. However, the exposure pathway remains unclear due to a lack of evidence on lead leachability from plastic to food.

- Traditional eyeliners have been linked to elevated blood lead levels, as documented in a large body of literature. Early regulatory efforts in South Asia suggest there may be an opportunity for impact, but the feasibility of a scalable intervention remains uncertain.

Based on this research, in late 2024, we decided to conduct a more in depth analysis of the potential impact of these four ideas in order to i) better prioritise our resources across them, ii) develop a draft intervention plan, and iii) identify the most important questions we need to answer in the field. We expect to run pilot programs on at least two of these sources in 2025. Other areas like metallic cookware, plastic toys, and Ayurvedic medicines show promise based on the shallow research exercise, but require further research to assess their scale and feasibility. We will research these opportunities in more depth in 2025.

Contributing to the formation of the Partnership for a Lead-Free Future

In September, on the sidelines of the 79th UN General Assembly, USAID and UNICEF launched the Partnership for a Lead-Free Future (PLF), which aims to end childhood lead poisoning by 2040. LEEP is proud to be a member of this partnership, and we were pleased to share our learnings with founding partners in the run-up to the launch, for example with President Obama and other leaders and philanthropists in March 2024. Our Head of Program Partnerships, Nafisatou Cissé, spoke about our approach to tackling lead exposure at the PLF launch.

Team growth

Our team grew from 10 to 19 in 2024. We were delighted to welcome Program Managers Joseph Chreim, Joel Fraser, Yujin Han, Hassam Khattak, Victoria Narancio Krauss, Srujith Lingala, and Dr Scott Kaba Matafwali; Juliette Finetti as Director of Research and Strategy; and Michael Beattie as Operations Associate, to the team.

Key metrics and impact

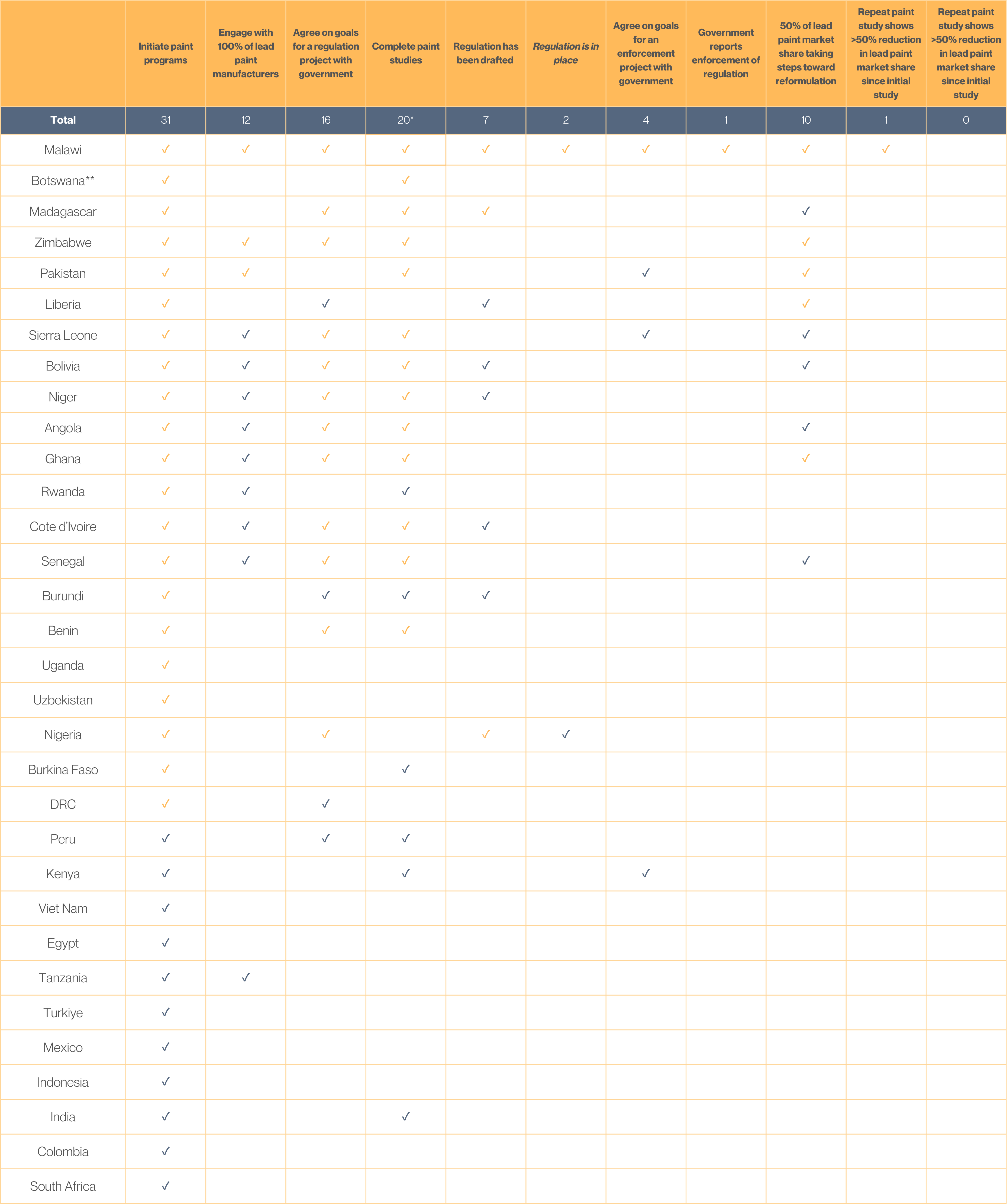

The table below summarises the status of our paint programs. Each column is an indicator of progress towards the outcome of reduced lead paint available on the market, and links to our theory of change (see graphic in ‘2025 goals’ section).

Figure 2: Summary of paint program statuses, with blue check marks indicating that the status was reached in 2024.

*We are currently unable to share identifying information about one of the paint studies.

**The paint study we conducted in Botswana in 2021 found that levels of lead were less than 100 ppm in all samples. We deprioritised work in Botswana as a result of these findings.

Did we meet our goals?

Our overall goal for our 2024 paint programs was to make a significant step to eliminate new lead paint across countries representing 45% of births in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). We define a significant step as having met an additional key goal, as laid out here. We’re really pleased to have hit this target, making significant steps in 20 programs, representing just over 45% of LMIC births and demonstrating that we can make progress on a large scale.

Counting up goals across individual programs, we generally fell short of totals we set for 2024. We believe this largely reflects overly ambitious goal-setting, rather than a fundamental issue with the feasibility of our programs or our team’s ability. We are taking a more bottom-up approach to goal-setting this year, more systematically incorporating input from the team members directly implementing the work, which we expect will result in more realistic targets moving forward.

In particular, we anticipated that regulation would be in place in more countries. Final approval is close in a few countries, and we have a good understanding of the last steps that need to happen. We have learnt how the final steps, such as a Minister signing the regulation, can take much longer than we expected, for example if there are log-jams with a large number of regulations to be signed.

We also undershot our goal for the greater than 50% of the lead market share reports taking active steps towards reformulating (we reached this in 10 countries, not 16). Despite being significantly below target, we’re quite happy with progress here. We have a reasonably good understanding of what it takes for a manufacturer to reformulate. However, it is quite time-consuming, often requiring lots of virtual communication and multiple in-person visits. We plan to hire in-country consultants more often, as well as an industry specialist in the program team to address this.

Cost-effectiveness and total impact

In 2024, we finalized our comprehensive cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) across 13 programs, building upon our initial 2021 model, and published our results. This updated analysis incorporates country-specific impact calculations, a significant improvement over previous estimates that relied on more generalized assumptions. We refined our estimates of manufacturer compliance rates, market penetration of lead-free paints, and the speed of regulatory adoption, leading to a more precise assessment of the program’s long-term effects.

This analysis has provided greater clarity on the key parameters that drive our cost-effectiveness, allowing us to refine our assumptions and be more transparent about how we derive our estimates. For example, because blood lead level (BLL) impact was a parameter our model was highly sensitive to, we developed an explainer document detailing our approach to estimating BLL changes from paint exposure, ensuring that our methodology is both rigorous and accessible.

Our latest analysis estimates that LEEP’s interventions across the 13 countries will prevent lead exposure in approximately 46.6 million children by 2100, averting an estimated 9.6 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). The projected economic benefit is also substantial, with an estimated $43.2 billion in lost earnings prevented across these countries. On average, these programs are estimated to avert one DALY-equivalent at a cost of $4.49, with a 90% confidence interval ranging from $0.78 to $12.93.

2025 goals

Paint programs

Our overall goal for our 2025 paint programs is to make a significant step to eliminate new lead paint across areas representing 35% of births in LMICs. Our key goals at the program level are laid out in the bottom half of the diagram below.

On sources of lead exposure other than paint, we aim to test interventions in at least five locations across multiple lead sources. For traditional eyeliners, we will assess the scale of lead exposure in four locations, pilot intervention strategies in two, and work with a public affairs consultancy to address regulatory barriers in one. For spices, we will conduct three lead content studies and collaborate with authorities to set intervention goals for addressing contamination in two locations. To support these efforts, we will hire generalist researchers to oversee studies and pilots, ensuring we build a strong evidence base for future program design.

Our 2025 goals are summarised here.

Financials

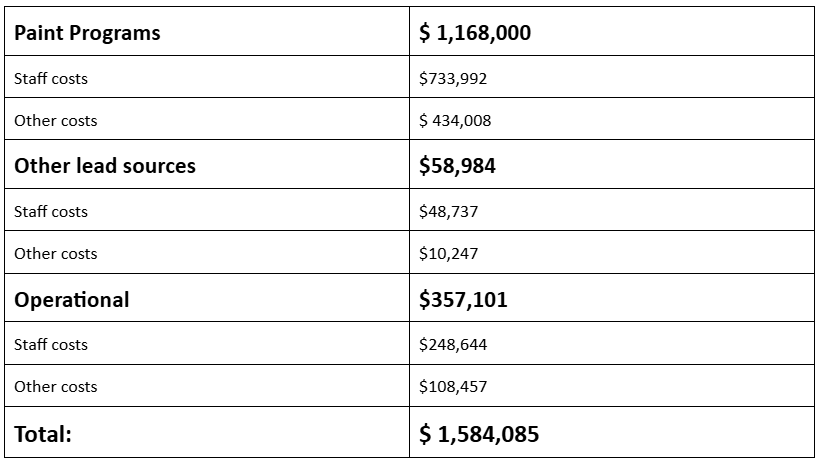

Expenses*

In 2024, we spent a total of $1,584,085.

*LEEP is currently undergoing its annual audit. Some of these numbers may not be exact and may be subject to change after the audit has been completed.

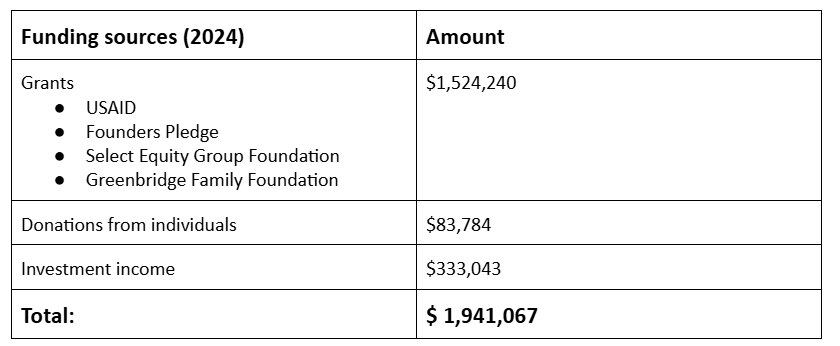

Funding

We are very grateful to have been supported by a number of institutions and individuals in 2024; more detail is provided in the table below. We are also delighted to have been awarded a $5 million fixed amount award by USAID in September 2024, to conduct paint programs across 33 countries worldwide over two years. At the time of publishing, we had received $1.3 million of this award. Given the current status of USAID, we are operating under the assumption that the project and associated funding will not continue. Fortunately, our unrestricted support from other donors has allowed us to continue without any significant disruption to our programs or goals.

As with last year, we aspire to fundraise for three years for each existing and new paint program. This allows us to make longer term plans and longer term commitments of support to our government partners. This will make it easier for our partners to commit to working towards well enforced regulation, and we expect that it will improve the efficiency of our programs.

Learnings

In this section, we briefly describe some additional lessons learnt through our paint programs over the period of this review.

Decorative, lead-containing spray paints appear to be widely available in LMICs

We have been including spray paints in our paint studies, and frequently find that they contain very high lead concentrations. For example, in Burundi, 33% of paint samples tested exceeded 90 ppm, with lead levels ranging from 910 ppm to 16,000 ppm. We have found similar results in Burkina Faso, Karnataka (India), Benin, and Niger. A 2020 study by EcoWaste Coalition, part of the IPEN network in the Philippines, found that 42% of spray paints tested had lead levels above 90 ppm. Notably, 33% of those had concentrations exceeding 10,000 ppm, with the highest sample containing 82,100 ppm of lead. Whilst the use case is often not made clear from the spray can, anecdotally we understand these are often used for decorative purposes, such as decorating indoor furniture, other household items, and canvas art. The risk they pose therefore seems significant. We will more systematically include spray paints in future studies and ensure they are addressed through our work with government and industry.

Enforcement of lead paint regulations requires a complex chain of coordinated actions

Through our work supporting regulatory authorities with lead paint enforcement, we’ve mapped the critical pathways within the regulatory implementation process. Effective enforcement depends on multiple interconnected steps (e.g. factory inspections, market surveillance, border checks, laboratory analysis and issuance of penalties) taken by different actors. Each stage can face challenges, e.g., inspectors may be unaware of which products are high-risk, and can struggle with resistant manufacturers who conceal certain products, or sample analysis could be delayed by insufficient testing capacity. This detailed understanding has refined our approach, using a variety of tools such as building testing capacity and providing training for inspectors, to ensure that every link in the enforcement chain is met.

Working with suppliers has accelerated our industry work

Access to lead-free raw materials remains a key barrier for many manufacturers. We have therefore been working more closely with suppliers of lead-free raw materials, and found that this work can help accelerate reformulation. For example, some suppliers have accelerated manufacturer reformulation through direct engagement after an introduction from LEEP; others have demonstrated the viability of their products at LEEP-organised reformulation workshops; and many have supported improved access by connecting manufacturers with local distributors.

Testing raw materials and paints during a manufacturer’s reformulation process can help ensure compliance

Working closely with manufacturers on paint reformulation has revealed important challenges in achieving consistent compliance with lead paint regulations. One issue is that lead may be present in supposedly lead-free materials. In one case, we tested a pigment labeled as “lead-free” that actually had a lead concentration of 4000 ppm. Another issue is that after replacing lead-based ingredients, we’ve found that some products still test slightly above the 90 ppm threshold due to equipment contamination. By testing raw materials and final products, we can support manufacturers to ensure genuine compliance and avoid unintentional contamination that could undermine their reformulation efforts.