Introduction from LEEP’s co-founders

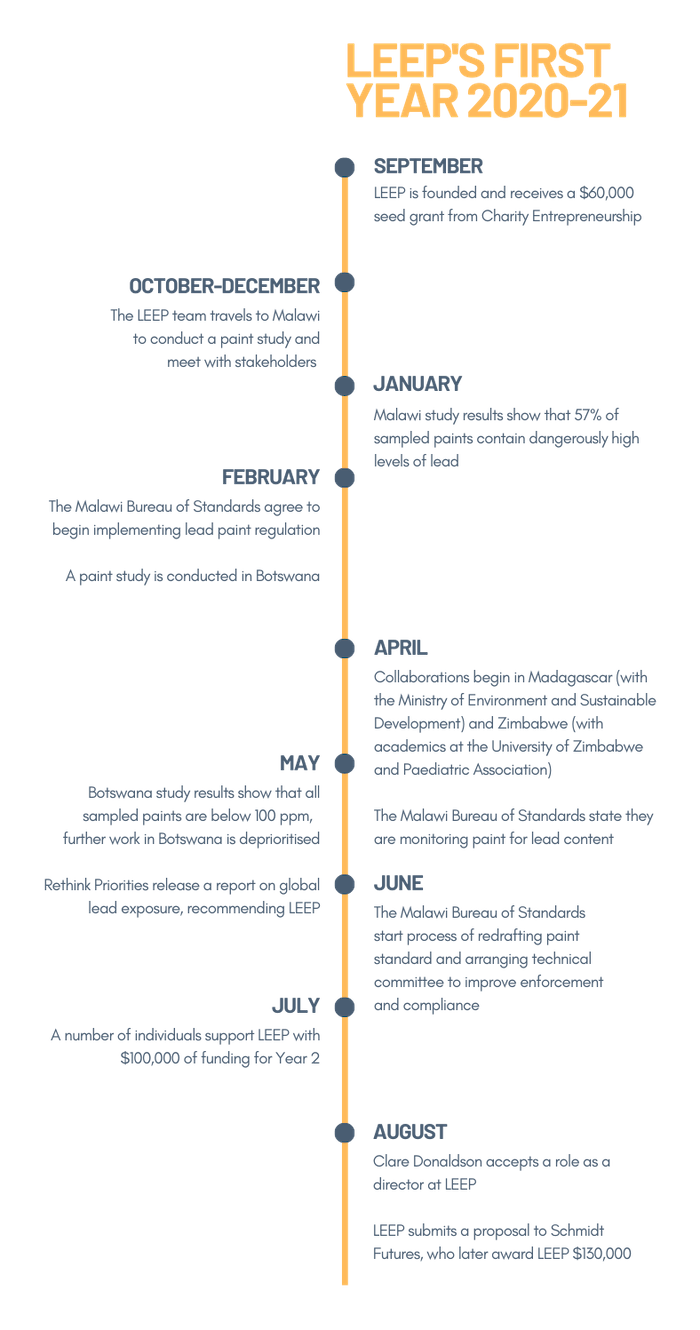

Around 1 in 3 children have lead poisoning globally and lead in paint is a major source of this exposure (UNICEF). Yet, lead is an unnecessary ingredient in paint, and regulations can successfully prevent its production (WHO & UNEP). As explained in our launch post, this motivated us to co-found LEEP in September 2020. We planned to advocate for the introduction and enforcement of lead paint regulation, with the aim of cost-effectively improving the health, wellbeing and future of millions of children.

We conducted a paint study in Malawi in late 2020 and presented the results to the Malawi Bureau of Standards, who responded quickly to the evidence and made a commitment to implement lead paint regulation. The Bureau of Standards stated that they have now started testing samples for lead, are arranging a technical committee to agree on a transition deadline, and will update the standard to make it more enforceable.

For this commitment to happen in the first six months of LEEP’s existence was a surprise and an encouraging achievement. We are grateful for the support from our partners at the Global Alliance to Eliminate Lead Paint, the mentorship from Charity Entrepreneurship, the advice of a number of lead exposure experts, and of course the dedication of officials at the Malawi Bureau of Standards.

Still, this is just a first step. There remains plenty of work to be done in Malawi in supporting the Bureau of Standards and industry with the switch to lead-free, and looking globally, hundreds of millions of childrens have lead poisoning at a blood lead level at or above 5 micrograms per decilitre (µg/dL).

We ended Year 1 on a high, fundraising enough for our second year’s ambitious plans to conduct paint studies in seven more countries and LEEP was one of two organizations working on lead exposure recommended by Rethink Priorities for funding.

Thank you to everyone who has supported us on our journey so far.

Jack and Lucia

Co-founders and co-directors

Summary metrics

- Country projects started: 4 (Malawi, Botswana, Madagascar, Zimbabwe)

- Paint studies completed: 2 (Malawi, Botswana)

- Meetings with government officials: 9 (Malawi)

- Meetings with paint manufacturers: 18 (Malawi)

- Commitments to implement lead paint regulations: 1 (Malawi)

What we set out to do in Year 1

In September 2020 our plan for Year 1 was to concentrate on one country. By the end of the year we hoped to have identified a promising focus country, built relationships with stakeholders, completed a paint sampling study, presented the evidence to government decision-makers and secured an agreement from government decision-makers to take action towards addressing lead in paint. We expected that in months 10-12 of Year 1 we would identify a potential second focus country and begin to build relationships with stakeholders there.

Our work in Year 1 (September 2020 – August 2021)

Malawi (September 2020 – )

Country identification and stakeholder engagement. LEEP identified Malawi as the first focus country in September 2020 and traveled there in October to begin engaging stakeholders. We established relationships with in-country experts (in health, policy, and research), government stakeholders, and industry. We met with the Malawi Ministry of Health (MoH) and Bureau of Standards (MBS), confirmed interest in the issue and gained approval for a study into lead paint. We found that MBS had existing standards banning lead in paint.

Paint testing. We then conducted a paint sampling study in collaboration with University of Malawi environmental scientists Mr Stanley Kaddamanja and supervisor Dr Ephraim Vunain. The study confirmed that solvent-based paints in Malawi contain high levels of lead (57% of those tested > 90ppm). Information from paint sellers suggested that solvent-based paints make up the majority of the market and that the local (lead-containing) brands are cheaper and more widely used than the imported (lead-free) brands.

Government outreach and traction. The next step was to present these results to MBS and MoH. In our meeting with the Director of Testing at MBS it was explained that they had not been monitoring for lead or enforcing the standard because it was not known that lead in paint was a problem. It was thought that lead in paint was an outdated ingredient and had already been phased out. As a result of the new data showing lead in paint they immediately took action to implement the regulation by incorporating lead testing into their twice yearly monitoring, with a plan to enforce compliance through their legally-binding certification scheme. They felt they had the capacity to enforce because they have the necessary lead analysis equipment and certification scheme in place. The director supported our plan for outreach to the paint industry and asked to be informed about our progress and the response from industry. MBS is now organising a technical committee with manufacturers to update the paint standard and agree on a transition timeline to improve enforcement and compliance.

Industry outreach. After that, our next main activity was industry outreach. We contacted the four local paint manufacturers to inform them of the finding of lead in their paint, the harms of lead paint, and the new monitoring and enforcement from MBS. All manufacturers engaged and expressed willingness to switch to lead-free paint if regulation is applied to all manufacturers. We identified that the main barrier is likely to be the initial cost of switching. We also collated information on locally available lead-free ingredients, their suppliers, and costs to provide to the manufacturers. We identified a paint technologist and reformulation expert to consult with manufacturers and facilitate reformulation.

Botswana (February – July 2021)

Country identification. In February 2021 we identified Botswana as a potential focus country – this choice was influenced by the pandemic, which restricted travel to other countries. Our main uncertainty was whether or not lead paint was available on the market in Botswana. We therefore started by conducting a paint sampling study instead of first investing time in stakeholder engagement.

Paint testing. Our study found that solvent-based paints for home use available on the market in Gaborone were primarily imported from South Africa, where regulation is already in place. Levels of lead in paint were less than 100ppm in all samples. This data was shared with academics involved in lead exposure research and further work in Botswana was deprioritised.

Madagascar (March 2020 – )

Country identification and stakeholder engagement. In March 2020 LEEP was introduced to Rila Albani Rakotomanana, Chief of Green Economy at the Ministry of Environment in Madagascar. The department had been advocating for lead paint regulation since 2018 and were preparing to draft a lead paint law. They believed that data on lead in paint in the country would significantly facilitate further progress with advocacy and increase motivation for enforcement and compliance. There had been no previous studies into the lead content of paint in Madagascar and the department had not yet managed to find funding or support for a paint study. In April LEEP therefore began a partnership with the department to provide the funding, study protocol, and technical guidance needed to generate the data. By the end of Year 1 (August 2021) the study is near completion, with 59 samples of paint collected.

Zimbabwe (April 2020 – )

Country identification and stakeholder engagement. In April 2020 we began a partnership with academic paediatricians from the University of Zimbabwe and Paediatric association, led by Professor Rose Kambarami. Before our involvement there was no research or advocacy ongoing and no previous research into the lead content of paint in Zimbabwe, but it was considered by our partners to be an important and highly neglected area. LEEP provided the funding, study protocol, and technical guidance, and our partners are working to engage the relevant stakeholders.

Operations

We began the US registration process to become a nonprofit corporation and then a 501(c)3 nonprofit. This will be enacted in our second year.

Key metrics

Country projects started

Paint studies completed

Meetings with government officials

Meetings with paint manufacturers

Commitments to implement lead paint regulations

Cost-effectiveness and impact

We made a cost-effectiveness model of LEEP’s intervention in Malawi. We included benefits to both health and income; made an assumption that the intervention brought forward regulation by eight years compared to the counterfactual scenario; and included LEEP’s predicted costs for work in Malawi over a 5-year period and the costs to the Malawian government. This document describes the April 2021 model and its key uncertainties in more detail.

We estimated that LEEP’s work in Malawi:

- will prevent lead poisoning of 262,000 children

- has a cost-effectiveness of $12/DALY-equivalent (90% confidence interval: 3-29 $/DALY-equivalent)

- brings about a total benefit of 76,000 DALY-equivalents over the next 20 years – with approximately 87% of the total benefits being due to increases in income, and 13% from health improvements.

[Edit: in January 2022 we published an updated model, updated accompanying documentation and a blog post contextualising the CEA. The updated results are 215,000 children, $14/DALY-equivalent and 43,000 DALY-equivalents (as described above).]

The model rests on various assumptions and should be interpreted cautiously. Further, there is uncertainty in applying this estimate to other circumstances; it’s possible that Malawi was particularly tractable. Nevertheless, this estimate of cost-effectiveness is very promising, and motivates us to expand and test the intervention in more countries.

Key learnings

Progress with governments may be faster than expected.

As described, the Bureau of Standards in Malawi committed to begin monitoring and enforcement of lead paint regulations (using pre-existing but unimplemented standards) within three months of LEEP’s advocacy beginning – significantly faster than our expected timeframe of one to two years.

Some factors that may have contributed to both the speed and level of engagement could be specific to lead paint regulation advocacy. For example:

- lead paint regulation is not particularly expensive for governments to implement or for paint manufacturers to comply with.

- there is a strong and established evidence-base for the harms from childhood lead poisoning.

- there is a global movement towards lead paint regulation, with successful implementation by a number of low- and middle-income countries and the support of international bodies such as the WHO. Other factors are mentioned in some of the next key learnings.

Although progress in Malawi has been faster than expected it is unclear how broadly this will generalise, and an important goal for our second year is to demonstrate replicability.

Country-specific evidence in the form of a paint study is an effective way to build traction

We believe a key reason for the speed of engagement from the Malawi Bureau of Standards was the new country-specific data on lead paint that we generated – this provided an effective opener to communications and demonstrated that lead paint is a problem in Malawi. Our government contacts confirmed that this Malawi-specific evidence was key for their decision to take action.

The existence of legally-binding regulation may not be sufficient

This was not a major surprise, but it was something we had not fully appreciated when starting LEEP. We initially expected our focus would be in countries with no legally-binding lead paint regulation. However, our experience in Malawi demonstrated that the presence of legally-binding lead paint standards does not necessarily equate to low levels of lead paint on the market. In Malawi there was no monitoring or enforcement for lead in paint because it was not known to be a problem, and there were no major incentives for manufacturers to produce non-lead paint. From having conversations with experts and reading a few studies that have been carried out after the introduction of regulation, we expect there are many countries where, for a variety of reasons, lead paint regulation is not being fully complied with.

A variety of partnership structures are possible

The covid-19 pandemic meant that we were unable to travel in early 2021 to conduct paint studies and meet stakeholders in-person. Instead, we facilitated studies remotely, by engaging with and then supporting partners in Madagascar and Zimbabwe. This has been valuable experience for LEEP, since remote partnerships may be a useful model in future, for example, in countries where English is not the official language.

Further, we have so far engaged with stakeholders in academia and various government ministries (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Environment, and others may also be relevant), and we expect that we will be able to partner with NGOs as well in future. The costs from lead poisoning are multifaceted, which means there are potentially several avenues with which to build partnerships.

Financials

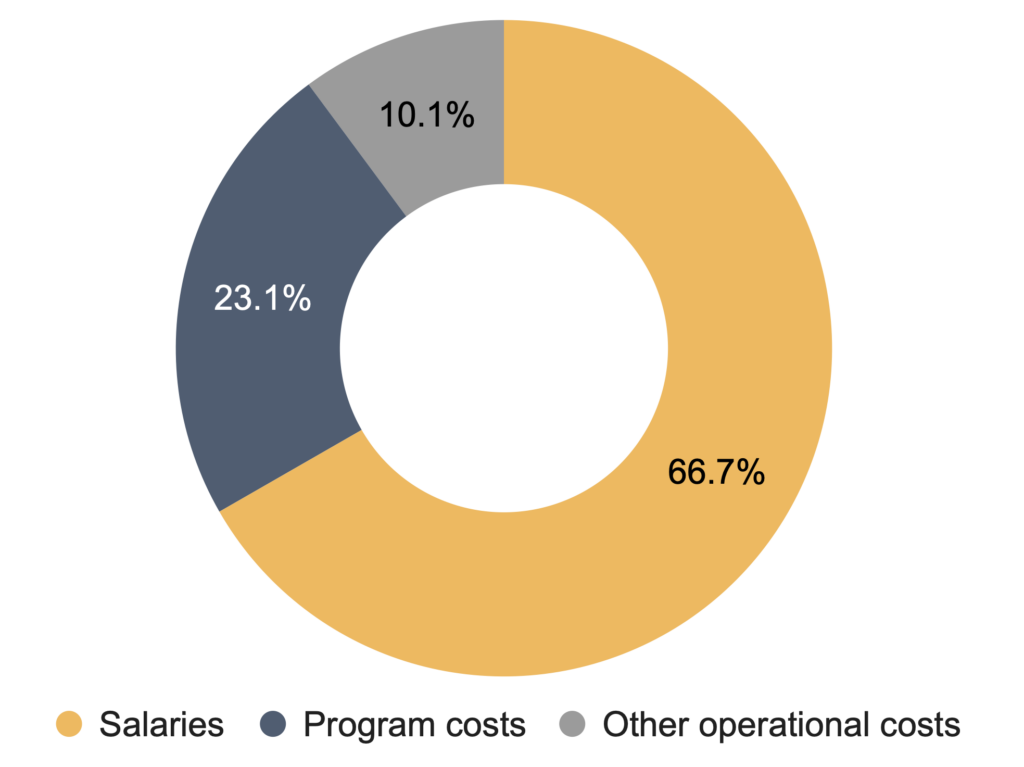

In Year 1, we spent a total of $73,292, which can be broken down into the following:

- Salaries: $48,754

- Program costs (including flights and travel, paint samples, lab paint tests): $16,920

- Other operational costs and administrative expenses (including fiscal sponsorship fees, filing fees and third party processing fees such as transaction fees to accept donations): $7,416

A Statement of Activities can be seen here.

Our funding for Year 1 mostly came from a seed grant from Charity Entrepreneurship ($60,000). In Year 1, we also received $96,210 from individual donors, almost all of which will go towards funding our second year of operations.

Plans for Year 2

Our Objectives and Key Results for Year 2 (September 2021 – August 2022) can be seen here, and a budget here.

The core plan is to complete paint studies in at least seven countries this year, and begin advocacy in the countries where lead paint is found to be available – likely prioritising those countries where engagement with the government appears tractable. In each country, we plan to partner with local groups, such as NGOs, academics or government ministries. An important goal is to demonstrate that the progress in Malawi is achievable elsewhere and gain commitments from two further countries to introduce or newly enforce lead paint regulations.

To expand our capacity for this work, at the end of Year 1 we hired Clare Donaldson as a Director of LEEP, joining Jack and Lucia on the leadership team. Clare’s dedication to having an impact, as well as her previous experience in the nonprofit sector and academic research, will greatly contribute to LEEP’s progress.

As part of our outreach in new countries, we want to explore different circumstances and contexts, in order to learn more about possible approaches. For example, we plan to conduct a paint study in at least one country that already has legally-binding lead paint regulation in place, and – if lead paint is still found to be available – explore supporting the government with effective enforcement.

We will also continue to work with partners in Malawi, with a further aim of ensuring that lead paint is effectively phased out. We will participate in a technical committee meeting organised by the Bureau of Standards and work with manufacturers, providing technical assistance to enable them to reformulate to lead-free paint. We are uncertain about the most effective ways of supporting industry to switch to lead-free, so this work will be important in developing our future strategy.

We will consider testing other sources of lead poisoning – such as food spices, which can absorb lead from the environment and sometimes have lead added to them to enhance their colour and weight. Whilst we want to remain focussed on our primary intervention, it may be possible to collect additional data while conducting a paint study, with little additional effort.

Finally, as part of a five-year plan, we intend to explore instigating changes at a global level around lead exposure, such as by strengthening collaboration amongst global partners working on lead exposure, or by advocating for more blood lead level data to be collected – for example, by including blood sampling in existing large-scale surveys. Our thoughts on this are in the early stages, but we hope to look into potentially high-leverage opportunities through the year.

Thank you to everyone who has supported us and made our first year possible, including our partners, mentors, volunteers and in particular our donors.